Transitioning a Product team to a Platform team

To maturity and beyond!

Version Control forms an integral part of any collaborative product, especially in the SaaS space. At Postman, the Version Control squad is responsible for building out these workflows and the underlying system which ends up powering core use cases of collaboration. Currently, Version Control is responsible for building out the

Fork, Diff, Merge and the Pull Request experience

Collection and Schema Changelog

Watching

Early days (MVP Stage)

When the team was formed during the squad formation exercise back in 2019 in lieu of the Domain Driven Design (add a link for this) exercise that we did at Postman, we were four people in the team.

If you think about Version Control, the first thing you would probably be thinking about is Git. Git has been able to revolutionise the idea of change management and change tracking. We wanted to do a similar thing for API development.

Postman’s vision was simple.

Make it easy for people to work with APIs.

Using this vision as our north star, we came up with the following guidelines while in the MVP stage.

1. Start with enabling a single use case

We started with Collections since that was the most used feature in Postman after History. Basic Version Control features include change tracking and change management. And, that’s what we started with.

For quite a long time, we only offered Changelog on Collections, and the ability to Fork, Diff and Merge Collections.

By focussing on a limited surface area, we were able to spend all our efforts into making the best version of changelog and forking. Since both of them were new features, we needed to validate it against our customers. So our primary focus was on talking to users and gathering feedback. This meant not only talking to external users but also people within Postman.

Dog fooding has always been a critical part of how we operate at Postman, so employees using the product on a daily basis was natural.

2. Iterate Fast

We had just started our journey into the Domain Driven Design world, but for us, in the MVP stage, thinking about domains and abstractions meant slower velocity. We had the final say in what the experience looked like and we opted for full independence and isolation.

Our main goal was to have a working product in front of the users to get feedback and fail fast. In order to achieve that, we had to cross the boundary between domains and understand each and every domain in depth. Having this knowledge allowed us to take action at our will rather than being blocked on another squad fulfilling our requirements for us. We ended up contributing to code that belonged to a different team to solve for our use cases.

A good example of this was the diffing engine we built for Collections. Since we wanted to provide a custom experience to the user, we understood each and every attribute that Collections offered to better evaluate what would be best for the end user. Having this knowledge allowed us to make changes on the go without having to wait for the Collections team. We also ended up improving the performance of certain APIs from Collections to make our experience faster.

If you iterate fast, engineering maturity naturally takes a back seat. Most of our engineering decisions were around how quickly we could build incrementally and independently. This should not be considered a bad way of working. Products or teams or companies in early stages need to make sure whatever they are working on is wanted. If you spend a long time working on the first cut of your product that uses cutting edge technology, is highly scalable, without bugs, even then it’s highly possible that your ideas and hypothesis do not align with what the user needs.

The end user does not care about any fancy tech you might be using internally to build the product. They care about the problem being solved through a usable experience.

3. Close to the product

Existing source control systems usually are a layer on top of your code. Your code can still work even if you don’t have Git initialised in a folder.

For us, we wanted to follow a similar philosophy from an engineering perspective, but wanted to be closer when it came to the product. Since the vision of Postman is to make working with APIs simple, it meant that we want to cater to people from all backgrounds. Developers. People Managers. Product Managers. Designers. CXOs. You name it. In the API First world, everybody will have to work with APIs to make their product successful.

Git only supports line based diffing, which means you can only diff two files or blobs line by line and then be able to see the difference between the two. All Postman elements have a JSON representation, but seeing the difference between two JSON structures in a line by line fashion is a pretty bad experience. Our aim was to improve this experience and make it simpler for all kinds of users to be able to work with Version Control, and be able to provide an experience much closer to how they use Postman elements.

For a Collection, suppose, if I’m creating a new request or a folder, instead of showing multiple lines in a Git based diff which make no sense, the ideal experience would be showing it in the same way how we show requests or folders in Postman.

Growth Stage

Across the pandemic, Version Control, both as the product and the team, grew.

We expanded our product offerings. We released Pull Requests, added Changelog for Schemas and introduced Forking for Environments. We also released a new product, Watching, which allows users to get notified when a change occurs.

On the people front, we hired around 70% of our current team size and grew to a team size of 8 on the engineering front.

We were beaming with new users, solving newer challenges both at a product and an engineering level. We now had enterprise users using our features which added more fuel to our fire.

But as one Ben Parker, famously said, “With great power, comes great responsibility”, our responsibility around maintaining the maturity of the system increased. We started to see cracks in the way we were functioning.

Zero Extensibility

Since we were relying on code that we had written, it meant that we also had to be on top of changes that were now being introduced with our downstream services.

All squads were in their full swing to deliver features and make the product better, which meant that most of our time went in understanding the impact of each change and then incorporating it into our system.

The other problem was onboarding newer teams. Onboarding them meant more work for us to now understand how they function and again do a full in depth analysis like we were doing while we were in the MVP stage. Ideally, we wanted to spend most of our time making our systems more reliable and building more features, but sadly we were just not able to.

One great example was when we had to onboard forking for environments. Most of our time went into how our existing system would even work with a new element type. Plus, while understanding more about environments we realised we had to do a lot more work around encryption and storage than we were even thinking about earlier.

Bugs, bugs and more bugs

As more and more features were being shipped out by other teams, it became practically impossible for us to be on top of all the changes. This meant that our offerings soon went out of sync with the changes made by other teams.

We had a plethora of bugs reported every week which were mainly around either inconsistency in data representation. Most of our time every sprint went into talking to the relevant teams and fixing all the issues that were being encountered.

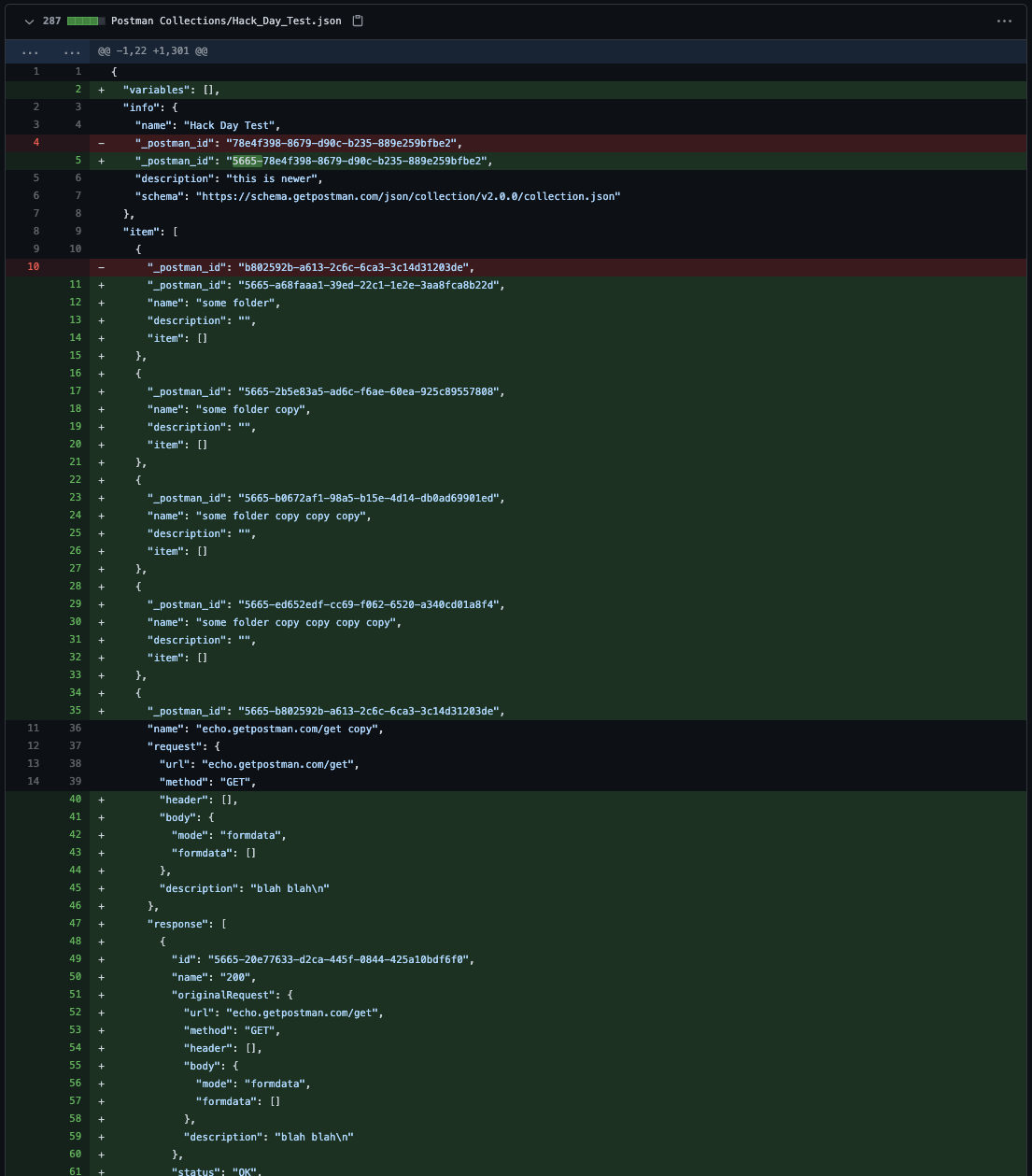

One such example, was when we had to deal with a few escalations on a daily basis because of a new attribute being added to the Collection structure, which we did not account for in our diffing logic, which meant the data became inconsistent.

Tight Coupling

Since we were aware of the full internals of their system, we had cut some corners during the MVP stage by tightly coupling our code with other team’s code.

Tight Coupling can bite you in the back especially when you start growing towards the mature stage. Any sort of such coupling means that neither of the two teams were able to work in isolation and always had to account for the other team’s changes when thinking about their own functionality. It soon became a cyclic dependency which was unable to handle.

For example, for Changelog, the Collections team was fully aware of how we were storing changes in the DB and was also directly making calls to the DB to read or write data. This meant that we could not make any schema related changes to our tables without ensuring that it would not affect the Collections team.

The Way Ahead

With so many issues cropping up, we needed to rethink how the Version Control system would be built out in a fashion where all teams could still use our features, be disconnected with how we have built our systems and have full control to modify certain behaviour at their own will. This leads to our guiding principles that we formulated during the API First exercise.

Make it generic

Whenever you think about when to make your system generic, the one major rule to follow is “The Rule of Three”.

The core principle of the Rule of Three is that you should limit genericisation until you have enough information to do it properly, and until the complexity of maintaining separate solutions is high enough.

We were already dealing with three consumers with Collections, Environments and APIs as the primary use cases. So, it made sense for us to use this rule and start thinking about how we generalise the system. If we had gone this route earlier, we would not have enough information on which aspects need to be generalised and fallen prey to premature generalisation. We did not even know if this was a solution required by more than one team.

The first major aim for us is to remove any tight couplings. Any tight coupling always makes you think twice whenever you plan to take on newer feature set. With us not being dependent on any other team to understand their domain, and them not having any information about our internals, it made a lot of sense to invest in APIs that could get the job done and still maintain a level of abstraction.

It will be easier and faster for us to build features without worrying about a different domain’s technical context. And, also for the other team to be able to modify behaviour without having us in the picture.

One such example of bad coupling, like I mentioned earlier, was our diffing engine. Since we had made it customly for Collections, it meant that we had to write a new engine each and every time a new element wanted to integrate with us. Instead, we decided to build a Schema Agnostic Diffing system, which would take decisions at runtime based on a predefined schema, controlled by the consumer directly. This allows the consumer to make changes to the schema without our involvement and gives them full control of how they want to version their element.

Performance is key

Building any product, the one major thing to always keep in mind, is the user experience. A bad user experience always leaves the user in a frustrating mood which would make them not use the product ever again later.

For us, performance plays a key role because we, by nature of our system, always have to deal with objects of varying sizes. You can create a collection containing a single request as well as 1000 requests. There are no restrictions. Having this constraint meant we had to rethink how our flows would work. We could not rely on our downstream services always to be performant because dealing with large objects is always a concern for all systems.

Instead of a synchronous flow, we decided to go for an asynchronous workflow to improve the perceived user performance. Async flows ensure that users get feedback quicker than having to wait for the entire operation to complete and then get an acknowledgement. So, in case you are merging a ton of changes to a collection, we modify the flow to inform you whenever the merge is complete and let you focus on other things instead of waiting for the merge to be completed and blocking you from performing any other action.

Easy to consume

The first thing that you comes to your mind whenever it comes to integrating with a newer API or interface is documentation and how easy would it be for you to consume the API.

We want to be in a position where it’s extremely simple for our consumers to integrate our system with theirs and get things up and running in a short period of time. Joyce Lin, Head of Developer Relations at Postman, talks about how the most important API metric is Time to First Call. In order to achieve this, we went for:

Playbooks

Create Playbooks that consumers can use, with little or no effort from our end, to get them registered on our platform.

One such example is our playbook for Watching. It covers how a consumer could register their element for Watching and all the APIs and components needed to enable the functionality.

End to End APIs

Since we were building for the entire Postman product, the experience of Version Control for all elements had to be uniform. We cannot have the PR experience show up differently for Collections as compared to Environments. This, along with, easier consumption meant we would enable Web APIs as well as Client Components and Interfaces that consumers could embed directly without worrying about the internals of how these interfaces/components work.

We took some inspiration from Aether and decided to build smart components on the client, which would do all the heavy lifting of making API calls to the backend services and provide a consistent experience based on a very simple configuration provided by the consumer.

We are in the middle of doing this. You can check out a demo for the new Diffing Representation here.

Change in mentality of the team

We started off as a Product focussed team by owning all user experiences end to end and focalising on a handful of consumers. With this shift towards building a Platform, the team mentality requires a change.

Earlier when we could get away with writing not so sustainable APIs or non performant code because we were the only consumers, will not work when we take the plunge into the Platform world. We need to make sure we have APIs well documented with proper SLAs and mechanisms for providing help and support for consumers. Documentation is required from day one, it does not have to be perfect.

Thinking like a Platform requires us to think about extensibility for everything. How would consumers make changes to their configuration without involving us? How can we think about all features while thinking about possible consumers in the future?

A really good example here would be thinking about how we handle cross squad requests. The mentality shift requires us to start thinking about how we can automate all such requests and remove human interaction completely.

Final Notes

As we take this plunge to start our journey towards a Mature squad, there are a lot of learnings that we encountered during our journey which helped us frame our vision better and increase our impact bit by bit.

The Product to Platform journey is not a necessity for all systems or teams. Teams can still operate in the Product zone while still catering to more than one consumer. The decision to start operating as a Platform stems from the idea around how scalable you want your team and system to become.